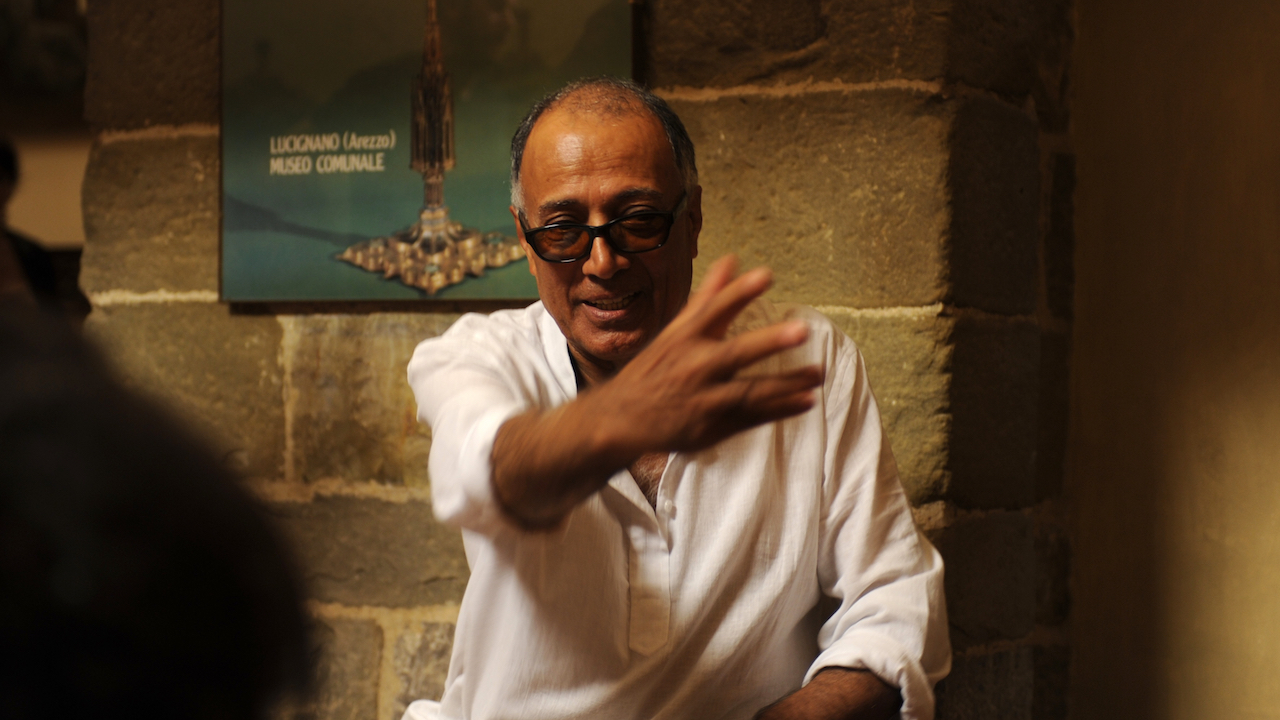

Abbas Kiarostami: Themes

Abbas Kiarostami’s Cinematic Themes

By critic Godfrey Cheshire on the occasion of Abbas Kiarostami: A Retrospective (Jul 26 – Aug 15, 2019)

A PROTEAN CREATOR

The initial idea for 24 Frames — Abbas Kiarostami’s final work, which essentially consists of twenty-four short films of roughly four and a half minutes each—came from the director’s observation that, in looking at a painting of a scene from the world, the viewer sees only a split second in time and is left to wonder what came before and after, and what the artist added or removed. Kiarostami started out the project by digitally extending the time frames of several paintings (only one of these, Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s The Hunters in the Snow, is seen in the final film) before turning to his own photographs for source material. In making such extensive use of computer-generated imagery, 24 Frames represented yet another creative leap for an artist whose career was full of them. And although Kiarostami did not intend the film, which he worked on intensively in the three years prior to his death in 2016, to be his last, it serves as a fitting final testament in its bringing together of so many of the interests and creative avenues he explored over the course of his long and multifaceted career. Several of these themes and forms are highlighted below.

PAINTING AND ILLUSTRATION

The son of a decorative housepainter, Kiarostami won a painting competition at age eighteen and majored in painting and graphic design at the University of Tehran School of Fine Arts, going on to work for a time as an illustrator and designer. He maintained a lifelong interest in the visual arts and counted a number of prominent artists among his friends. In a sense, the digital tools used for 24 Frames allowed him to combine his skills as a filmmaker with his passion for drawing and illustration.

ART AND MUSEUMS

Kiarostami was interested in the ways art is presented publicly and the creative possibilities afforded by the museum context. In the latter part of his career, he created a number of installations for museums and galleries around the world. Some of these explored subjects—such as doors, mirrors, frames, and trees—taken up elsewhere in his work. Though Kiarostami considered 24 Frames to be a film, he considered it a companion piece to his installations and photography exhibitions and felt it could work in a gallery or museum setting.

CHILDREN

Kids are at the center of many Kiarostami films. Early shorts such as Bread and Alley, Breaktime (1972), and A Wedding Suit (1976), as well as the feature The Traveler, center on youthful conundrums and subjectivities, and feature the striking performances by young actors for which Kiarostami became known. The director’s films during this period, including the education documentaries First Graders and Homework, also reflected his experiences and concerns in raising his young sons Ahmad and Bahman. Kiarostami said that he and other directors chose to focus on children after the Iranian Revolution to avoid the obstacles that the Islamic Republic’s censorship laws put in front of filmmakers wanting to offer realistic depictions of grown men and women. In making 24 Frames, he had young viewers in mind, saying he thought they might enjoy the film’s visual playfulness.

NATURE AND PHOTOGRAPHY

Throughout his adult life, Kiarostami devoted considerable energy to his love of photography, and his photographs were displayed in galleries around the world as well as published in a number of books. Nature was his favorite and most frequent subject. While he took pictures in many of the countries he visited, his best-known photographs are of the landscapes and roads of his native Iran, images that resemble some of the scenes in films such as And Life Goes On, Through the Olive Trees, and The Wind Will Carry Us. And nature offered Kiarostami more than just subjects for his photos. Ahmad Kiarostami has said his father “‘cleaned his eyes with nature’—he used that expression. He had to go into nature. His ideal trip was to go alone, or with one friend, just driving in the mountains and taking pictures.” All but one of the “frames” in 24 Frames derive directly from one or more Kiarostami photographs of the natural world.

POETRY

Kiarostami not only read and memorized vast quantities of verse, Iranian and international, classical and modern; he also wrote it voluminously. (In the Shadow of Trees: The Collected Poetry of Abbas Kiarostami, a nearly seven-hundred-page volume of English translations by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, was recently published in the U.S.) In cinema, poetry served Kiarostami in two ways. It gave him ideas and words, including the titles of Where Is the Friend’s House? and The Wind Will Carry Us, both of them phrases borrowed from modern Iranian poets. Additionally, poetry gave Kiarostami models for formal strategies in his films right up until 24 Frames, including the use of visual “rhymes” and ellipses.

IMAGINATION

In his celebrated feature Close-up, Kiarostami told the story of a man who attempted to escape his constricted life by posing as a famous film director. Kiarostami said the tale illustrated that art and imagination can release people from the difficulties that the world imposes. In cinema, Kiarostami often indicated that he felt limited by the budgets, technology, and need for crews that came with moviemaking. In making use of digital imagery for 24 Frames, he freed himself—and the viewer—to travel to places bounded only by the limits of imagination itself.

IFC Center does not generally provide advisories about subject matter or potentially triggering content in films, as sensitivities vary from person to person. In addition to the synopses, trailers and other links on our website, further information about content and age-appropriateness for specific films can be found on Common Sense Media, IMDb and DoesTheDogDie.com as well as through general internet searches.